Mayank Patel

Sep 15, 2025

5 min read

Last updated Sep 15, 2025

Every ecommerce team wants higher conversions. But too often, optimization eff orts rely on guesswork—redesigning a button here, changing copy there—without clear evidence of what actually moves the needle. This results in sporadic wins at best and wasted effort at worst.

The most effective CRO programs don’t chase random ideas; they follow a system. They start with careful observation of user behavior, enrich those signals with analytics and feedback, form structured hypotheses, and run disciplined experiments.

Heatmaps, session recordings, form analytics, and funnel data are powerful tools, but they’re only valuable when used to generate focused hypotheses you can test. This guide walks you through that end-to-end process: how to map user behavior, enrich signals, frame testable ideas, experiment without pitfalls, and scale what works.

The first step is observation. Mapping what users actually do on your site. This involves using tools to visualize and record user interactions. By capturing how visitors navigate pages, where they click, how far they scroll, and where they get stuck, you build a factual baseline of current UX performance. Key behavior-mapping tools include:

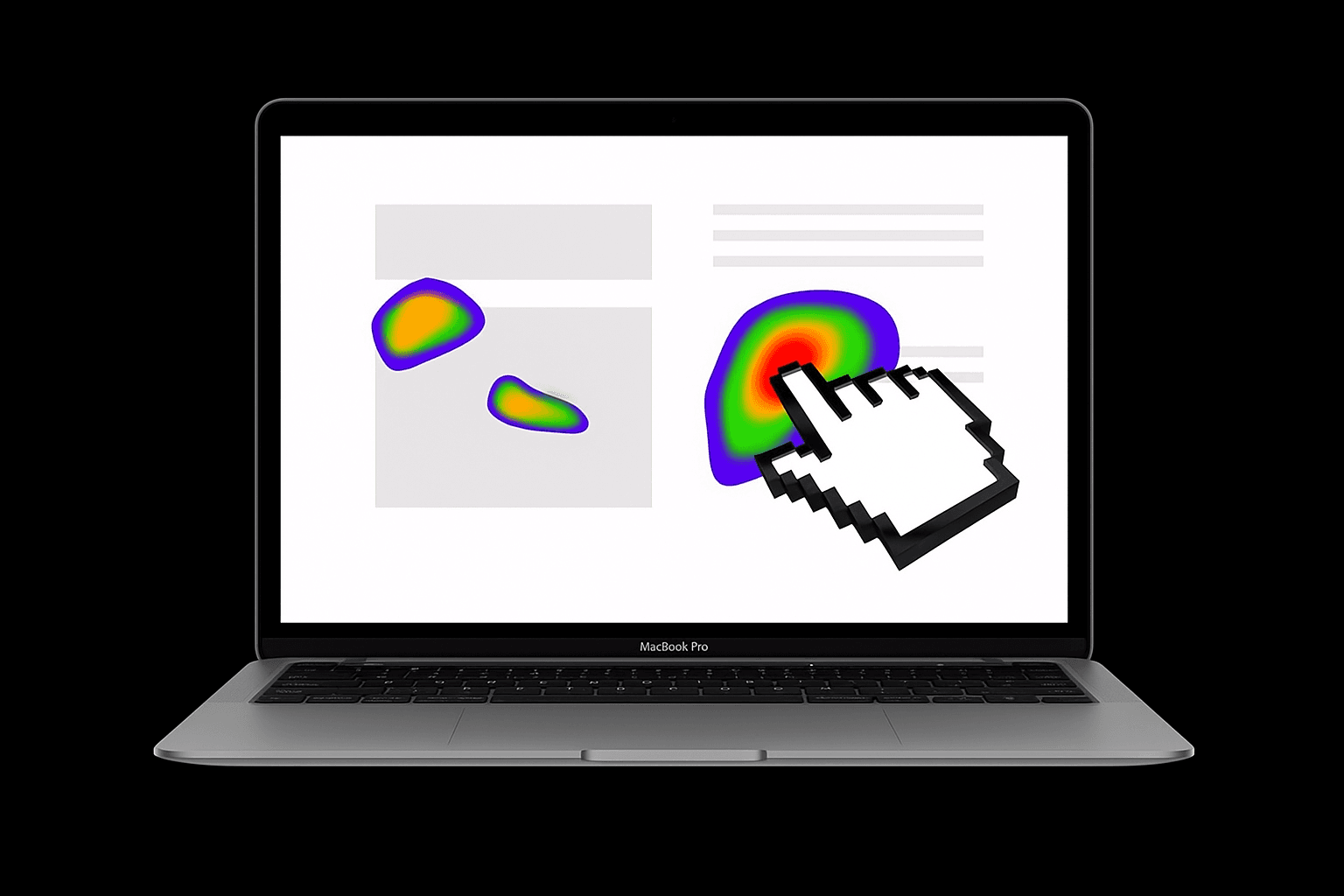

Visual overlays that show where users click, move their cursor, or spend time on a page. Hot colors indicate areas of high attention or clicks, while cool colors show low engagement. If a CTA or important link is in a “cool” zone with few clicks, it might be poorly placed or not visible enough.

A specialized heatmap showing how far down users scroll on a page. This reveals what proportion of visitors see each section of content. In practice, user attention drops sharply below the fold. If a scroll map shows that only 20% of users reach a critical product detail or signup form, that content is effectively unseen by the majority. This observation signals a potential layout or content hierarchy issue.

These capture real user sessions as videos. You can watch how visitors browse, where they hesitate, and what causes them to leave. Session replays are like a “virtual usability lab” at scale, for example, a user repeatedly clicking an image that isn’t clickable (a sign of confusion), or moving their mouse erratically before abandoning the cart (a sign of frustration).

By reviewing recordings, patterns emerge (e.g. many users rage-clicking a certain element or repeatedly hovering over an unclear icon). Establish a consistent process for reviewing replays (for instance, log “raw findings” in a spreadsheet with notes on each observed issue) so that subjective interpretation is minimized and recurring issues can be quantified.

Specialized tracking of form interactions (e.g. checkout or sign-up forms). Form analytics show where users drop off in a multi-step form, which fi elds cause errors or timeouts, and how long it takes to complete fi elds. For example, if many users abandon the “Shipping Address” step or take too long on “Credit Card Number,” those fi elds might be causing friction.

After gathering behavioral data, the next step is enriching that data. This is where we transition from what users are doing (quantitative data) to why they’re doing it (qualitative context).

Key enrichment methods include:

Quantitative analytics (from tools like Google Analytics or similar) help size the impact of observed behaviors. They answer questions like: How many users experience this issue? Where in the funnel do most users drop off ? For example, a heatmap might show a few clicks on a “Add to Cart” button but analytics can tell us that the page’s conversion rate is only 2%, and perhaps that 80% of users drop off before even seeing the button.

Analytics can also correlate behavior with outcomes: e.g. “Users who used the search bar converted 2X more often.” These metrics highlight which observed patterns are truly hurting performance. They also help prioritize a problem affecting 50% of visitors (e.g. a homepage issue) is more urgent than one affecting 5%.

Breaking down data by visitor segments (device, traffic source, new vs. returning customers, geography, etc.) enriches the signals by showing who is affected. Often, averages hide divergent behaviors. For instance, segmentation might reveal that the conversion rate on desktop is 3.2% but on mobile only 1.8%, implying mobile users face more friction (common causes: smaller screens, slower load times, less convenient input).

Or perhaps new visitors click certain homepage elements far more than returning users do. By segmenting heatmaps or funnels, patterns emerge. For example, mobile visitors might scroll less and miss content due to screen length, or international users might struggle with a location-specific element. These insights guide more targeted hypotheses (maybe the issue is primarily on mobile, so test a mobile-specific change).

Sometimes the best way to learn “why” users behaved a certain way is to ask them. Targeted surveys and feedback polls can be deployed at strategic points. For example, an exit-intent survey when a user drops out of checkout (“What prevented you from completing your purchase today?”). Or an on-page poll after a user scrolls through a product page without adding to cart (“Did you find the information you were looking for?”).

Survey responses often highlight frictions or doubts. For example, “The shipping cost was shown too late” or “I couldn’t find reviews.” These qualitative signals explain the observed behavior (e.g. “why did 60% abandon on shipping step?”). Even language from customers can be valuable; if multiple users say “the form is too long,” that’s a clear direction for hypothesis. User reviews and customer service inquiries are another VoC source.

In addition to direct user feedback, an expert UX/CRO audit can enrich signals by identifying known usability issues that might explain user behavior. For example, if session replays show users repeatedly clicking an image, a UX heuristic would note that the image isn’t clickable but looks like it should be (violating the principle of affordance). While this is more expert-driven than data-driven, it helps generate potential causes for the observed friction which can then be tested.

The result of signal enrichment is a more complete problem diagnosis. We combine the quantitative (“how many, how often, where”) with the qualitative (“why, in what way, what’s the user sentiment”) to turn raw observations into actionable insights. Quant data may tell us that users are struggling, but it doesn’t tell us what specific problems they encountered or how to fi x them, for that, qualitative insights are needed.

Likewise, qualitative anecdotes alone can be misleading if not quantified. Thus, a core LinearCommerce strategy is to triangulate data. Every hypothesis should ideally be backed by multiple evidence sources (e.x. “Analytics show a 70% drop-off on Step 2 and session recordings show confusion and survey feedback cites ‘form is too long’”). When multiple signals point to the same issue, you’ve found a high-confidence target for optimization.

Also Read: How to Engineer Cloud Cost Savings with Kubernetes

With a clear problem insight in hand, we move to forming an hypothesis. A hypothesis is a testable proposition for how changing something on the site will affect user behavior and metrics. Crafting a strong hypothesis helps you run experiments that are grounded in rationale, focused on a single change, and tied to measurable outcomes.

In the LinearCommerce framework, a good hypothesis has several key characteristics:

The hypothesis must directly address the observed problem with a cause-and-effect idea. We don’t test random ideas or “flashy” redesigns in isolation. We propose a change because of specific evidence.

For example: “Because heatmaps show the CTA is barely seen by users (only 20% scroll far enough) and many users abandon mid-page, we believe that moving the CTA higher on the page will increase click-through to the next step.” This draws a clear line from observation to proposed solution.

Defi ne exactly what you will change and where. Vague hypotheses (“improve the checkout experience”) are not actionable. Instead: “Adding a progress indicator at the top of the checkout page” or “Changing the ‘Buy Now’ button color from green to orange on the product page” are concrete changes.

Being specific is important both for designing the test and for interpreting results. Each hypothesis should generally test one primary change at a time, so that a positive or negative result can be attributed to that change. (Multivariate tests are an advanced method to test multiple changes simultaneously, but even then each factor is explicitly defined.)

A hypothesis should state the expected outcome in terms of user behavior and the metric you’ll use to measure it. In other words, what KPI will move if the hypothesis is correct? For example: “…will result in an increase in checkout completion rate” or “…will reduce form error submissions by 20%”. It’s important for you to pick a primary metric aligned with your overall goal.

If your goal is more purchases, the primary metric might be conversion rate or revenue per visitor; not just clicks or time on page, which are secondary. Defining the metric in the hypothesis keeps the team focused on what success looks like.

Pitfall to avoid: choosing a metric that doesn’t truly reflect business value (e.g. click rate on a button might go up, but if it doesn’t lead to more sales, was it a meaningful improvement?). Teams must agree on what they are optimizing for and use a metric that predicts long-term value. For instance, optimizing for short-term clicks at the expense of user frustration is not a win.

A helpful format for writing hypotheses is:

“Because we see (data/insight A), we believe that changing (element B) will result in (desired effect C), which we will measure by (metric D).”

For example: “Because 18% of users abandon at the shipping form (data), we believe that simplifying the checkout to one page (change) will increase completion rate (effect), as measured by checkout conversion% (metric).”

After writing hypotheses, prioritize them.

You’ll generate many hypothesis ideas (often added to a backlog or experimentation roadmap). Not all can be tested at once, so rank them by factors like impact (how much improvement you expect, how many users affected), confidence (how strong the evidence is), and eff ort (development and design complexity).

A popular prioritization framework is ICE: Impact, Confidence, Ease. For instance, a hypothesis addressing a major dropout point with strong supporting data and a simple UI tweak would score high (and likely be tested before a hypothesis about a minor cosmetic change) rather than falling for the HIPPO effect (Highest Paid Person’s Opinion) or pet projects without data.

With hypotheses defined, we proceed to experimentation, where we run controlled tests to validate (or refute) our hypotheses. A disciplined experimentation process is crucial: it’s how we separate ideas that actually improve conversion from those that don’t. Below are best practices for running experiments, as well as common pitfalls to avoid.

The most common approach is an A/B test; splitting traffic between Version A (control, the current experience) and Version B (variant with the change) to measure differences in user behavior. A/B tests are powerful because they isolate the effect of the change by randomizing users into groups.

For more complex scenarios, you might use A/B/n (multiple variants) or multivariate tests (testing combinations of multiple changes simultaneously), but these require larger traffic to reach significance. If traffic is limited, sequential testing (rolling out a change and comparing before/after, carefully accounting for seasonality) could be considered, though it’s less rigorous.

In any case, the experiment design should align with the hypothesis: test on the specified audience (e.g. mobile users if hypothesis was mobile-focused), run for the planned duration, and make sure you’re capturing the defined metrics (set up event tracking or goals if needed).

Perhaps the biggest testing pitfalls are statistical in nature. It’s essential to let the test run long enough to gather sufficient sample size and reach statistical significance for your primary metric. Ending a test too early, for example, stopping as soon as you see a positive uptick can lead to false positives (noise being mistaken for a real win). This is known as the “peeking” problem.

To avoid this, determine in advance the needed sample or test duration based on baseline conversion rates and the minimal detectable lift you care about. Use statistical calculators or tools that enforce significance thresholds. Remember that randomness is always at play; a standard threshold is 95% confidence to call a winner.

Before trusting the outcome, verify the experiment was implemented correctly. Check for SRM (Sample Ratio Mismatch) if you intended a 50/50 traffic split but one variant got significantly more/less traffic, that’s a red flag that something is technically wrong (e.g. bucketing issue or flicker causing users to drop out).

Also monitor for tracking errors. If conversion events didn’t fi re correctly, the results could be invalid. It’s wise to run an A/A test on your platform occasionally or use built-in checks to ensure the system isn’t skewing data. Quality checks include looking at engagement metrics in each group (they should be similar if only one change was made) and ensuring no external factors (marketing campaigns, outages) coincided only with one variant.

Robust experimentation culture invests in detecting these issues, for example, capping extremely large outlier purchases that can skew revenue metrics or filtering bot traffic (which can be surprisingly high). Garbage in, garbage out; a CRO test is only as good as the integrity of its data.

When the test period ends (or you’ve hit the required sample size), analyze the outcome with an open and scientific mind. Did the variant achieve the expected lift on the primary metric? How about secondary metrics or any guardrail metrics (e.g. it increased conversion but did it impact average order value or customer satisfaction)? It’s possible a change “wins” for the primary KPI but has unintended side effects (for example, a UX change increases sign-ups but also spikes customer support tickets).

Always segment the results as well. A variant might perform differently for different segments. Perhaps the new design improved conversions for new users but had no effect on returning users. Or it helped mobile but not desktop. These nuances can generate new hypotheses or tell you to deploy a change only for a certain segment. Avoid confirmation bias: don’t only look for data that confirms your hypothesis; also ask “what does the evidence truly say?” If the test showed no significant change, that's learning too.

A quick summary:

A single A/B test can yield a nice lift; a CRO system yields compound gains over time by constantly learning and iterating. This stage involves institutionalizing the practices from the first four steps, managing a pipeline of experiments, feeding lessons back into the strategy, and ensuring your CRO eff orts mesh with the broader e-commerce stack.

Think of the CRO process as a loop: Observe → Hypothesize → Experiment → Learn → (back to) Observe…. After an experiment concludes, you gather learnings which often lead to new observations or questions. For example, a test result might reveal a new user behavior to investigate (“Variant B won, suggesting users prefer the simpler form but we noticed mobile users still lagged, let’s observe their sessions more”).

Successful optimization programs embrace this loop. After implementing a winning change, immediately consider what the next step is, perhaps that win opens up another bottleneck to address. Conversely, if a test was inconclusive, dig into qualitative insights to guide the next hypothesis. By closing the loop, you create a cycle of continuous improvement.

As you conduct observations and brainstorm hypotheses, maintain a CRO backlog (or experiment roadmap). This is a living list of all identified issues, ideas for improvement, and hypotheses, each tagged with priority, status, and supporting data. Treat this backlog similar to a product backlog.

Regularly update priorities based on recent test results or new business goals. For instance, if a recent test revealed a big opportunity in site search, hypotheses related to search might move up in priority. A well-managed backlog also prevents “idea loss,” good ideas that aren’t tested immediately are not forgotten; they remain queued with their rationale noted.

Scale Up What Works

When a test is successful, consider how to scale that improvement. Deploy the change in production (making sure it’s implemented cleanly and consistently). Then ask: can this insight be applied elsewhere? For instance, if simplifying the checkout boosted conversion, can similar simplification help on the account signup flow? Or if a new product page layout worked for one category, should we extend it to other categories (with caution to test if contexts diff er)?

This is where CRO intersects with broader UX and product development. Good ideas found via testing can inform the global design system and UX guidelines. Integrate the winning elements into your design templates, style guides, and development sprints so that other projects naturally use those proven best practices.